Margaret Wolfe Hamilton Hungerford coined the phrase, “beauty is in the eye of the beholder”. After hearing these words repeated time and again, a saying has never been truer than when it comes to the shifting ideals of beauty over time and across cultures. Beauty is relative, but unanimously relative. Throughout history, the model of beauty has been shaped for thousands of years due to religion, economics, art, music, politics, and all other elements combined to create a culture of humanity continuing to evolve from its ancestors years, decades, or even multiple centuries later. What comprises the perfect beauty aesthetically changes with time, yet the determination to achieve the ideal beauty remains the same, despite the century and geographic location a person exists in.

|

| Lady Lillith |

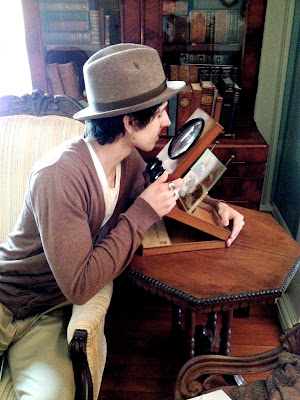

In Ancient Egypt, “beauty was a concept related to ma'at, the order that Egyptian's saw in their world”. To Egyptians, hair, apart from on the head, symbolized impurity. In order to guarantee they weren’t impure, men and women removed all of the hair on their bodies in addition to the hair on their heads. Instead of growing their own hair, they wore wigs as a substitute. Even prostitutes were expected to remove all of their hair because otherwise, they were considered unclean to sleep with Egyptian men. Youthfulness was another beauty ideal for Ancient Egyptians. "They used multiple types of oils that were specifically designed to stave off dry skin, minimize the look of scar tissue, and maintain the overall illusion of youth”. The use of eye makeup by Egyptians was considered beautiful, but it also repelled insects, warded off bacteria, and protected women and men from the sun’s rays (which would obviously affect their youthful appearance). Hair played an important role that shaped beauty in Ancient Egypt. It was “considered an extension of an individual's sexuality”. Thus, wigs were preferred as hair because they could be dyed and styled in any manner an Egyptian man or woman desired.

|

| Egyptian Women Applying Makeup |

|

| Aphrodite |

In Ancient Greece, the ideal beauty fluctuated and didn’t entirely revolve around physical appearance. The Delphic Oracle claimed “the most beautiful is the most just." Greek art demonstrates the model of beauty as one in moderation, harmony, and symmetry. The concept of ideal proportions was a result of the Greek classical standards of beauty, “derived from symmetry and a modular relationship, of the parts to the whole on a mathematical basis.” In addition, Plato’s “golden proportion” details the ideal face as one that has width two thirds of its length. Yet, the Greeks’ magnetism towards symmetry was counterbalanced with two other beauty concepts: fertility and youth. A woman in Ancient Greece represented youth and fertility by growing out her hair and dyeing it blonde.

|

| Pompeii Mural Reproduction |

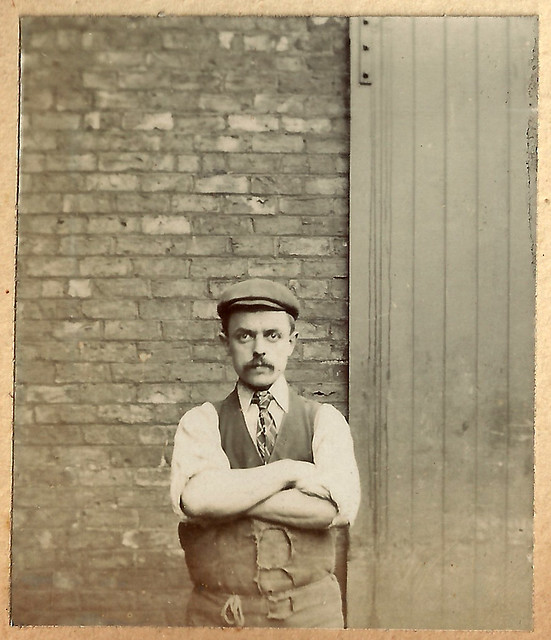

Ideal beauty in Ancient Rome is determined from poetry, sculptures, frescoes, and literature. Martial, an Ancient Roman poet, wrote, “I fear big-breasted women,” which was translated to the size of a woman’s breasts in Roman sculptures. Nymphs and goddesses also had small bosoms with each breast able to fit in one hand. Additionally, Roman frescoes detail women having petite chests, but large derrieres and thighs. The women deemed the most beautiful had sizeable backsides in Ancient Roman times. In literature, Petronius’ description in Satyricon (126) depicts the perfect woman’s face as one with a small forehead, curved nose, and a unibrow. “No speech could describe her beauty. Her eyebrows run right from the edges of her cheekbones and almost meet above her eyes. Her nose is slightly hooked and her little mouth as kissable as Praxiteles’ Diana." Accordingly, Ancient Roman beauty is composed of small breasts, considerable posteriors, little foreheads, connected eyebrows, and dignified noses.

|

| The Gift of the Heart |

With the arrival of the Middle Ages, ideal beauty fundamentally changed. In the Early Middle Ages, the followers of a strict Christianity refused to flaunt their bodies and physical looks. Nudity was believed to be sinful. Consequently, women wore shapeless clothes and head coverings. However, there was an ideal female silhouette. She needed to have a high waist and protruding belly because it denoted fertility, which was coveted in the time period. Purity and innocence were values that went hand in hand with Christianity, shaping the idyllic beauty to include paleness and a nonexistence of cosmetics. Nevertheless, as the quality of life improved with the movement to the High and Late Middle Ages, female beauty was noted once again. Mimicked by women in the Middle Ages from the Medieval tapestry, The Gift of the Heart, the perfect woman was slim with narrow hips, a small bosom, and a silhouette resembling an S. Perfection still featured slenderness and pallor, but there was the addition of rosy cheeks by adding blush to exhibit a woman’s cheer. Roman de la Rose, a French poem from the 13th century, portrays the ultimate Medieval beauty as a woman who has a straight nose, a small mouth with plump red lips, and dimples on her cheeks and chin. Combined, the Early, High, and Late Middle Ages embraced innocence, fertility, and modesty as the ultimate qualities of beauty throughout the era.

During the Renaissance, beauty was recognized from two different perspectives that, to an outsider of the period, seem paradoxical. To illustrate, “beauty was an imitation of nature in accordance with established rules and as the contemplation of a supernatural degree of perception that could not be perceived by the eye because it wasn’t fully realized in the sublunary world.” Therefore, Neoplatonic imagery put emphasis on Venus as the ideal beauty, a prevalent representation that launched from Ficino’s reconstruction of mythology. To contrast with supernatural beauty ideals, poetry written by Petrarch highlighted the epitome of beauty during the Renaissance. She was required to have blonde hair, a high forehead, fair skin, and an elongated neck. To achieve this, a woman would dye her hair and pluck her hairline. Physical appearance mirrored how beautiful a woman was on the inside throughout the time period. Those living in the Renaissance believed “a woman's outward appearance and inner soul were inextricably linked, giving no credence to the adage that beauty is only skin deep.” Their beliefs were that if a woman was virtuous, she was beautiful. And physical beauty was evidence that she was virtuous.

|

| Portrait of a Woman |

When it comes to the 17th century, paintings were the major authority controlling the meaning of the ideal beauty of the era. Specifically, Peter Paul Rubens, a Flemish artist, painted countless nude women in the early 1600s with stout bodies including generous rears, small breasts, and large thighs, inspired by his own wife’s body. He was the most prolific painter during the Baroque era, forming the aesthetics women hoped to attain. The portly figure even became known as “Rubenesque” as a flattering adjective to depict a woman’s body with curves. Furthermore, the Baroque period was a time of extravagance and sumptuousness, which is easily translated into why the flawless beauty appeared naked in paintings while carrying extra weight on her body.

|

| Venus and Adonis |

|

| Queen Charlotte |

The 18th century took a different turn. This was known as the rational century, with an emphasis on the spread of knowledge, philosophy, intellect, and science. Also, common people looked to the aristocrats for beauty standards of the time. To reject naturalness from the prior century and emphasize an “out-of-this-world” viewpoint, women emphasized their “wasp” waists and accentuated their extensive “hips” with horizontal padding. Hair, too, took an unnatural form with far-reaching vertical heights and powdered white wigs to differ from natural darker hair colors. The higher the hair, the bigger the wig, and the more excessive the adornments amounted to beauty because they all exemplified the wealth of the woman in addition to the most “unnatural”.

Romantic beauty and Victorian beauty were two entirely contrasting beauty ideals in the 19th century. Romantic beauty was a result of the fall of aristocracy in France and a revival of nature, emotions, and imagination. Romanticism represented a reaction against the formal rigid style of the 18th century. “People were concerned more with content and less with form; they preferred to break rules." Correspondingly, beauty included long hair and chemise-inspired empire waist dresses for women. Beauty meant abandoning excessive fabric, atypical hairdos, and an obvious facade. “Many costumes showed conscious attempts to revive certain elements of historical dress” (such as Greek and Roman fashions). Alternatively, when Victoria became England’s queen in 1837, strict morality, religion, modesty, and control of sexuality were esteemed. Thus, cosmetics were abandoned because they were dubbed immoral. Throughout the rest of the 1800s while Queen Victoria reigned, a woman’s purpose was to serve and bear children for her “masculine” husband. Therefore, the ideal woman was delicate, womanly (in order to show she was fertile), sexually innocent, and fair-skinned. A woman achieved this by wearing a corset to compress the waist, by omitting all makeup, and by wearing a crinoline, petticoat, and eventually, a bustle, to show fertility as well as modesty.

|

|

Madame Juliette Récamier |

|

| Victorian Woman |

Lastly, the 20th century’s description of the model beauty changed from decade to decade instead of century to century, which was unlike any previous age. The 1920s were a rebellion against the severity and restrictions of the Victorian times. To starkly vary from the previous womanly and corseted silhouette, the ideal woman had a slim boyish figure and short bobbed hair. The advent of the admiration of film stars, dancing at nightclubs and speakeasies, and playing sports were all determinants of the ideal beauty. Upon the arrival of WWII, restrictions denied women elegant and feminine clothing. The common look amongst the middle class was utilitarian. For that reason, the supreme beauty was glamorous and womanly, inspired by the influence of film stars such as Veronica Lake and Rita Hayworth and Christian Dior’s New Look. After WWII, Dior’s New Look was revered and translated to an ideal beauty that was curvy with an hourglass figure, stimulated by media celebrities such as Bettie Page and Marilyn Monroe. “This era saw the launch of Playboy magazine and the idolization of the soft, coquettish woman with overt sexuality.”

|

| Louise Brooks |

|

| Rita Hayworth |

|

| Bettie Page |

In the second half of the 20th century, aesthetics significantly changed. The 60s saw fashion models gracing the covers of fashion magazines. One model in particular, Britain’s Twiggy, altered the perception of the model beauty. She was a “near-sickly” slim model who set the precedent of skinny equaling ultimate beauty during the decade. In the 1970s, however, natural beauty was worshipped as the essence of what was beautiful. The ultra skinny model was no more. Farrah Fawcett was considered the ideal beauty “with her blown-out waves and natural makeup, demonstrating a mixture of the hippie ideals and early disco trends marking the era.” The approach of the 80s shifted gears as women began gaining power in their own careers. But models on the covers of magazines, for instance, Brooke Shields, established the standards of idyllic beauty as an amalgamation of defined eyebrows, too much makeup, and immensely disheveled and inflated hair. From the 1990s until today, the ideal beauty has been recognized as stick-thin and “fit”. The fashion model, Cindy Crawford, because of her athletic figure featured in numerous magazines, brought this about. Moreover, the willowy Kate Moss started the trend of coveting skeletal models as well as skinny consumers in the 1990s, which still exists two decades later.

|

| Twiggy |

|

Farrah Fawcett

|

|

Brooke Shields

|

|

| Kate Moss |

To no surprise, the ideal beauty is relentlessly changing due to factors that characterize time periods and geographic locations. Whether it’s literature, religion, art, media, war, morals, the economy, beliefs, or celebrities, there’s a grounds for why the standards of beauty are modified or transformed from culture to culture. Undoubtedly, the perfect beauty is proportionate to the society it’s formed around. In the future, beauty will continue to be interpreted based on the civilization and the elements of the age. However, one motivation across cultures and generations will remain unchanged and in harmony: the drive to attain ideal beauty. Thus, to quote John Kenneth Galbraith, “there is certainly no absolute standard of beauty. That precisely is what makes its pursuit so interesting.”

Sources:

http://beautifulwithbrains.com/2010/08/06/beauty-in-the-victorian-age/

http://news.discovery.com/history/history-beauty-120412.html

http://www.metmuseum.org/learn/for-teens/teen-blog/renaissance-portrait/blog/the-ideal-woman

http://quotationsbook.com/quotes/author/2701/

http://www.thefashionspot.com/beauty/news/171133-beauty-ideals-throughout-the-ages/?slide=9

http://www.examiner.com/article/beauty-ancient-egypt

http://www.wondersandmarvels.com/2012/11/does-my-culus-look-big-bizarre-roman-beauty.html

http://www.oocities.org/sherli_cheryl/19thcentury.htm

http://www.paris-culture-guide.com/peter-paul-rubens.html

http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(01)06947-1/fulltext#article_upsell

http://www.cbsnews.com/2100-205_162-4822981.html

http://www.touregypt.net/featurestories/beauty.htm

http://www.evoscience.com/concept-women-beauty-centuries/

http://aarticles.net/culture-art-history/11837-kakim-byl-ideal-zhenskoj-krasoty-v-srednie-veka.htmlhttp://www.arthistoryarchive.com/arthistory/european/European-Ideal-Beauty-of-the-Human-Body-in Art.html